R.A.T.W. Page 1 1

Being a band that strives to be an entity unto itself these days is a can’t win situation; the public gives you trouble if you step outside your chosen format, yet they constantly demand new and better things from you and come down hard if you don’t deliver. The suspicion also lurks about dressing rooms that a band can never be the same if one of its members leaves after the group has achieved a modicum of success.

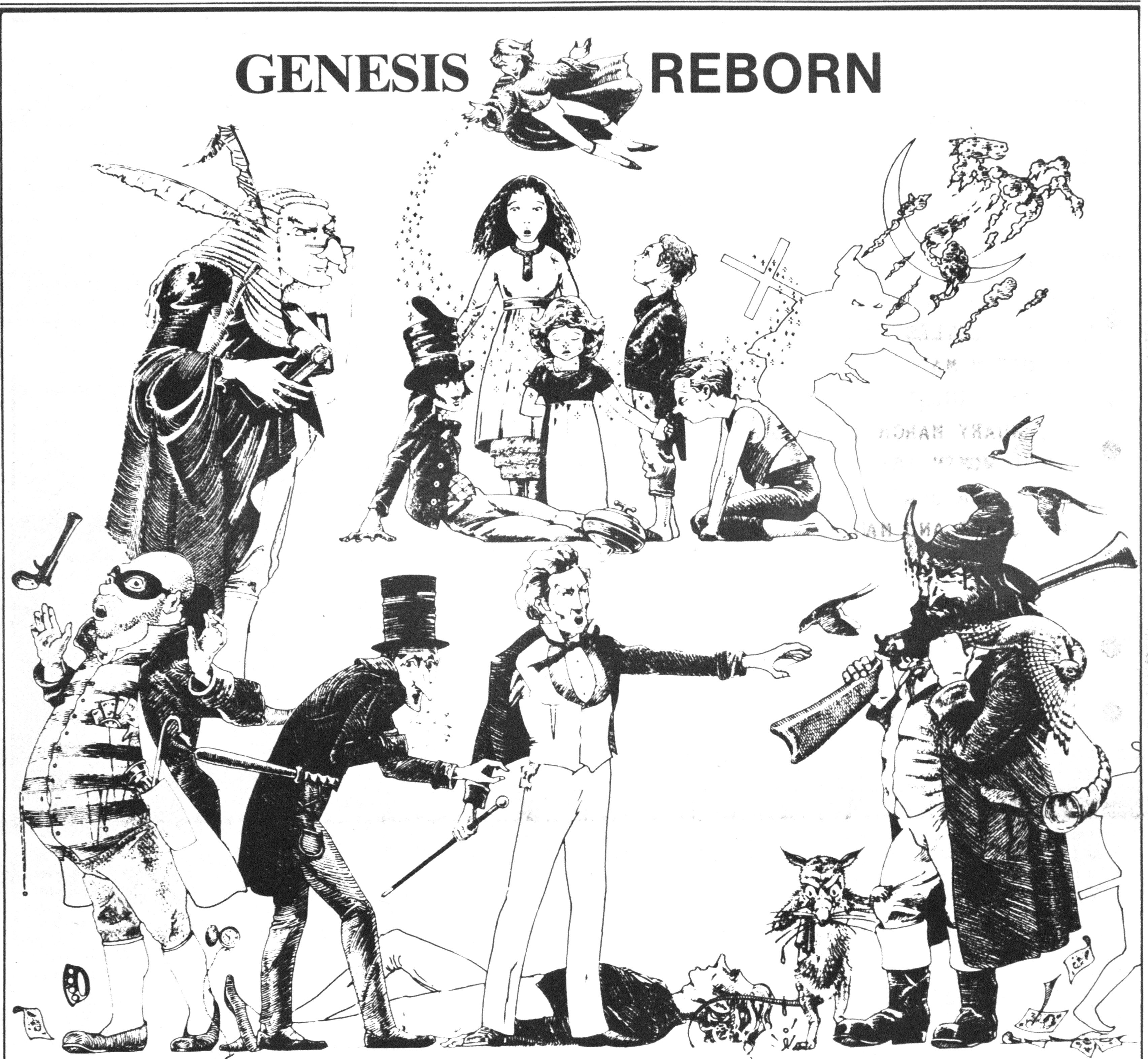

Such was the case with the ‘new’ Genesis; after spending roughly three years carving out their own private niche in the U.S. record market and developing a stage personna that relied heavily on each individual member, Peter Gabriel, the band’s lead singer, flutist and visual center of attraction with his costumes, masks, etc., left the band for reasons that have been well-catalogued by now. Genesis fanatics were shocked: how, they reasoned, can you replace an irreplaceable

member? Surely the new version of the band would never match what had already been done. When word from the Genesis camp arrived that the new singer was none other than Phil Collins, the band’s percussionist extraordinaire and second vocalist, and that on tour Bill Bruford would now handle most of the drumming, reaction was still mixed. People worried that Collins’ voice wasn’t strong enough to be out front, or that the band would be limited to a real short live show because they certainly wouldn’t have the audacity to try and perform material made famous by the band with Peter Gabriel.

Given all the hoop-la, controversy and circular argumentation surrounding the band, it was surprising, then, to discover that each individual member radiated an aura of confidence that previously had gone unnoticed; Mike Rutherford, the band’s bass player, second guitarist and back-up singer, noted that while this was certainly a new line-up for the band, there were indeed several links to the past: “I feel it’s like the old Genesis with a bit of fresh energy, because musically, it’s

a continuation for us . . . we’ve stretched ourselves more lyrically in certain areas to make up for any kind of loss on the writing spectrum, but I think it’s very much the Genesis direction.”

Ah yes, the Genesis direction, that tangled path the band has chosen to tread to achieve their musical ends; cluttered at every turn with creatures, beings and situations that defy explanation, the single unifying thread that holds it all together is the music. Even the running order of a Genesis album is structured to allow the fantasy room to develop. Tony Banks explains: “We normally have a pretty good idea about the structure. We try to plan an album so that it flows very well from track to track . . .”

An album is one thing; attending a Genesis performance and trying to assimilate all the different sensory inputs is quite another task. Surprisingly enough, though, Genesis has achieved great popularity in countries where English isn’t the chief language, like Italy and France. Both Mike Rutherford and Phil Collins believed that it was due principally to the music and the spell it weaves.

“Especially in places like Italy, when you go into a piece that might have six or seven different moods in it, they don’t understand the lyrics unless they know the song, and even then they only know the words in English. You’ll get ripples of applause from different parts of the auditorium from a mood change rather than an actual understanding of the words . . . they kind of go with the whole mood of the thing.” Tony adds that “. . . our songs are normally built from the music upwards, so that’s the foundation of the song. It’s what we consider to be strong in the first place.”

Still, it’s the lyrics that actually tell the story, and as such, bear the responsibility of making the audience understand what’s going on. How do creatures like the Squonk, the Slipperman or the Felon come into

existance then?

“1 think a lot of our lyrics come from what the music suggests to us; sometimes the music really does suggest what it shouldn’t be about, which often gives you what it should be about.”

What Genesis’ music is all about is life: their odd characters are odd only to us because they’re different from us. Who knows? Maybe the Squonk thinks we’re really weird, too. At any rate, where Genesis wheels and deals best is in the realm of fantasy, using their cast of oddities to tell us about ourselves. Portraying fantasy on stage is no little feat; the alliance of lights, costumes, film, effects and music is a tenuous one, always threatening to tip towards the overblown visuals. Genesis have more successfully kept that balance than anyone else, yet even they’re thinking that it can go too far.

Says Tony, “We once wanted to use anything that could be effective for us in the show. I think in the future we are thinking of possibly scaling down the visual presentation because it gets out of hand. I mean, we’ve done gigs without visuals, and it certainly makes no difference as far as the audience goes. In the end, you feel that maybe all the visuals aren’t really worth the bother because of the unreliability of it all. I think you can do just as effective a visual show using interesting lighting effects and things, if they’re very well thought out, and originally thought out.”

The core of Genesis remains intact; like a few other groups, there seems an air pervading this band that will ensure a certain definable entity known as Genesismusic regardless of the players. Mike Rutherford perhaps sums up best the feeling that being a member of Genesis brings: “I still think that I’m incredibly lucky, really, being able to make a living at something that obviously brings a lot of pleasure to me.” Los Endos.

—Jim Kozlowski